How I Spent My (East German) Summer Vacation

Kate Papageorge was a Collections Intern and will receive her master’s degree in Library and Information Studies this year from UCLA.

As a Collections Intern at the Wende Museum, I had the pleasure of cataloging fascinating objects that represented aspects of life during the Cold War. Many motifs emerged from the materials I processed and one in particular seemed apropos for a summer internship: vacationing.

The vacation theme burst forth from a shoebox one day as I was unpacking items from a recent shipment. I discoverered nearly 400 postcards, each of which was a record of someone’s journey, complete with place name, image, date, and commentary giving me a glimpse into the travels of the people living in the German Democratic Republic. Guided by these colorful images, I began to get a sense of what it was like for people there to go on vacation and was inspired to learn more.

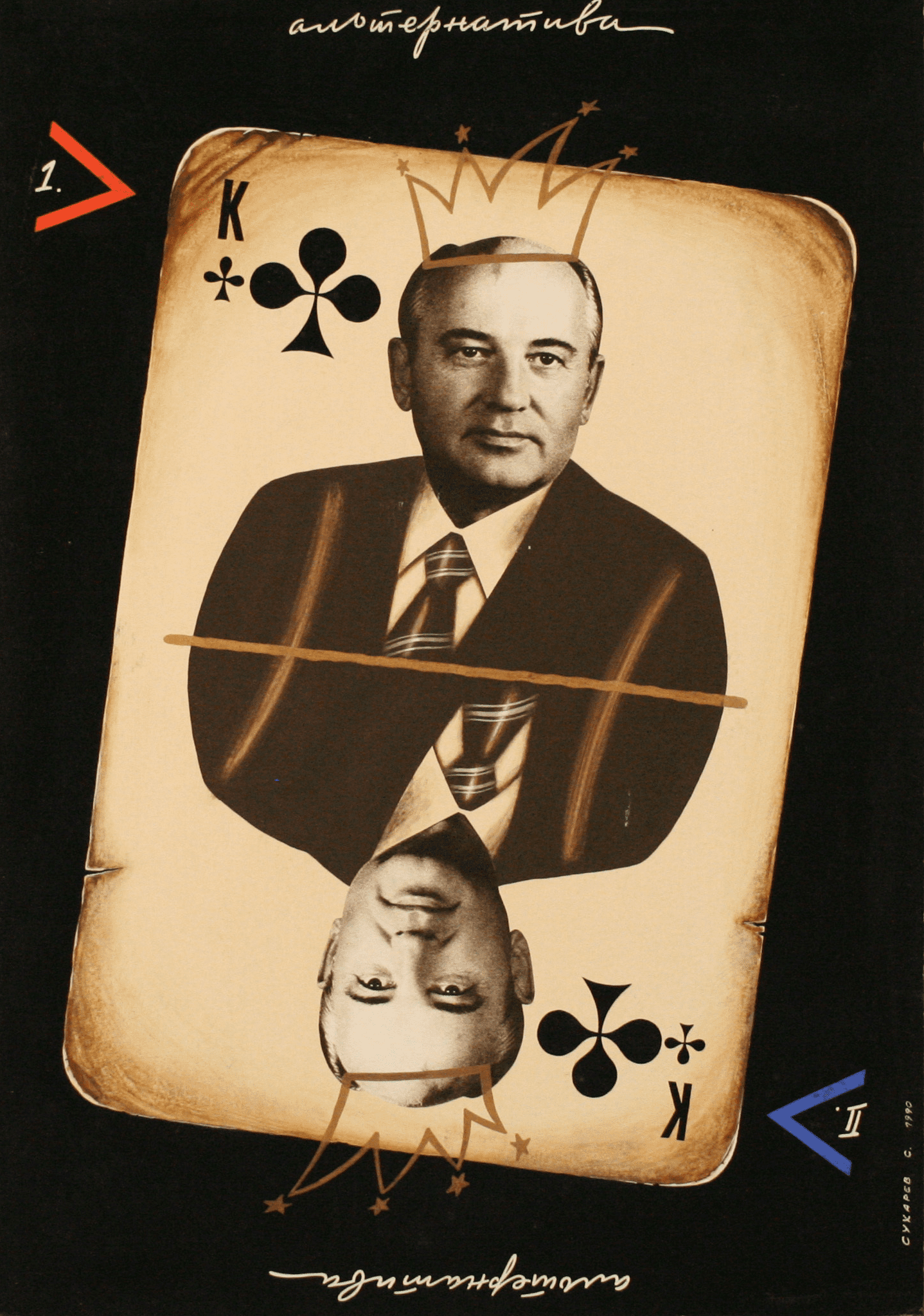

After some reading, it became clear that travel in East Germany was at once both restricted and facilitated by the political circumstances of the day. In a country where labor was assigned a great deal of importance, travel was seen as a way to rejuvenate oneself for the return to work. Thus the state made provisions for its citizens to enjoy an appropriate amount of travel and leisure time. To begin with, the labor reforms of the 20th century ensured that the citizens of the GDR had much more vacation time than they had historically, rising from 6 to 18 days during the country’s existence. Furthermore, state travel agencies like Reisebüro and union groups like the Freier Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund (FDGB, or Free German Trade Union Federation) helped to organize travel that was relatively easy and affordable, albeit to a limited number of locations. Large factories often operated their own resorts, which were available to workers at any level of the firm for a reasonable price.

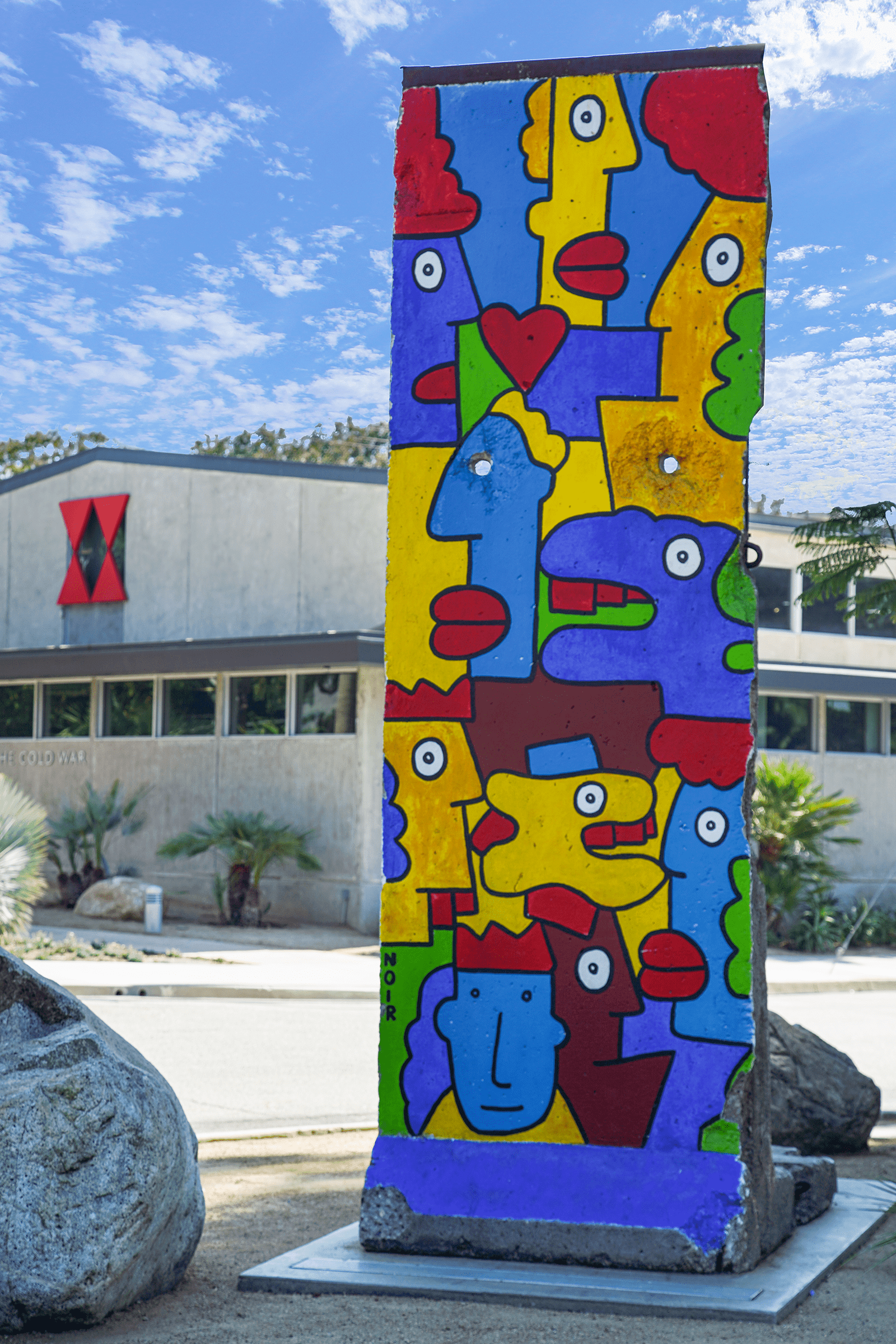

However, the freedom to take time off and the freedom to travel are not the same thing. Because the government restricted the movement of its citizens for political reasons, East-West travel involved lengthy and unpleasant encounters with the Grentztrupen (border guards) at border checkpoints. As a result, citizens of the GDR mostly traveled instead to friendlier areas in the Warsaw Pact region and also roamed extensively throughout their own countryside, visiting East Germany’s many attractions along the way. And so it was that GDR inhabitants would pack up their Trabants and head off into the wild and wonderful East.

Germany is notable for its multifarious tourist destinations. Boasting a combination of historical sites, modern cities, and vast swaths of natural beauty, Germans and international visitors alike had no shortage of vacation destinations to choose from. Some of the more popular vacation spots within East Germany were the Baltic Coast and the Saxon Mountains.

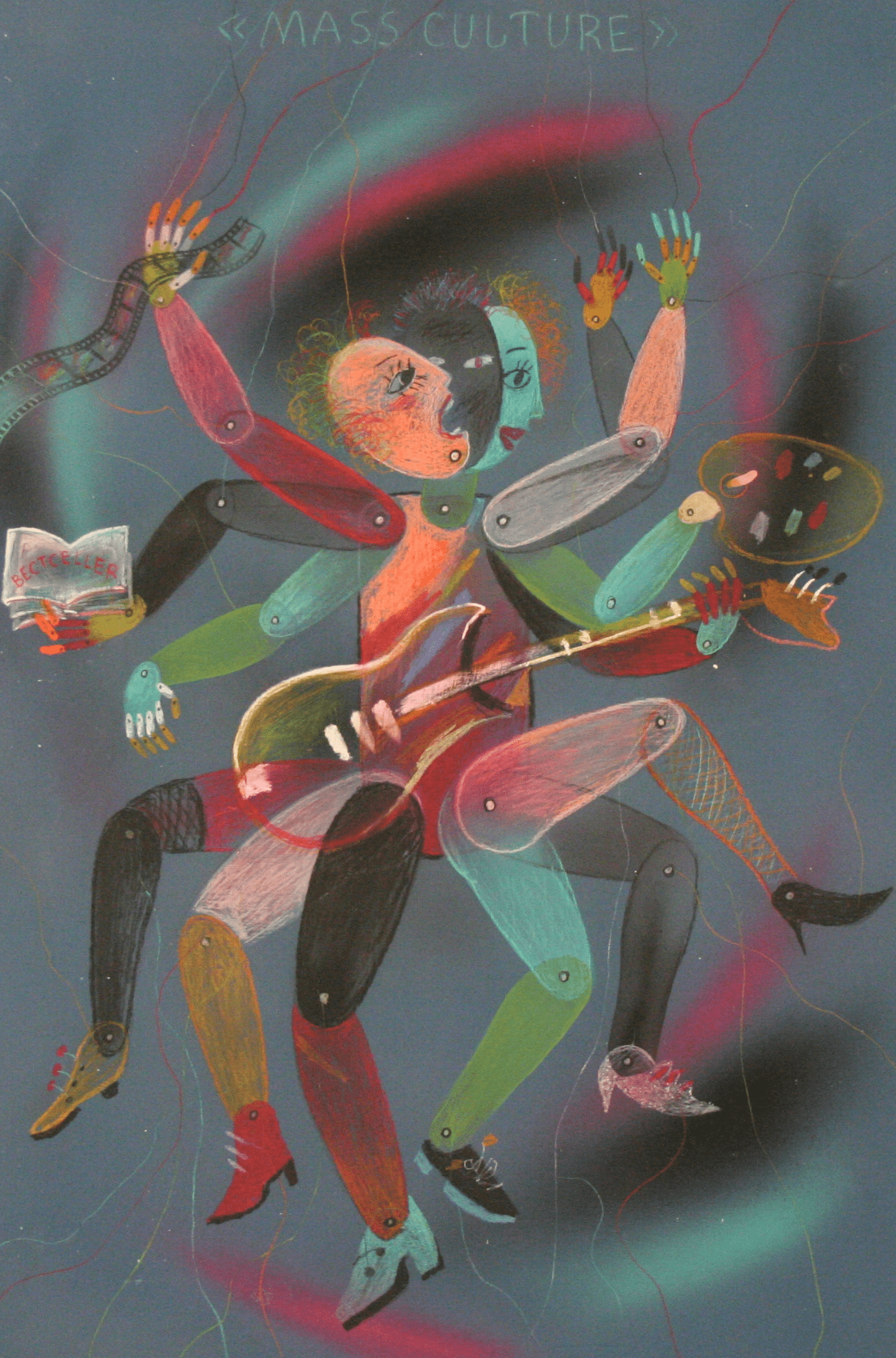

The general types of activities that took place on these vacations would be the same as any vacation in the West, but with the subtle yet pervasive differences that distinguish daily life on one side of the wall from the other. These typical vacation activities are evident from the different locales represented by the postcards in the collection I processed. The spa towns located throughout the country gave visitors an opportunity for rest and relaxation, while some of the challenging mountain ranges offered more strenuous recreation. Resorts frequently hosted summer and winter sports and historical sites were an opportunity to be informed and inspired. Lastly, the big cities of the German Democratic Republic, such as Dresden, Berlin, Potsdam, and Leipzig offered the culture, historical connection, and entertainment that tourists desired. The images on the postcards let us imagine ourselves as vacationers at the tourist attractions they advertise.

I have grown very appreciative of the practice of postcard sending. This ritual has created vast amounts of data on the travels of people from all walks of life. And yet, this commemorative tendency is not unique to writing postcards. Whether it is checking in on Facebook, sending a postcard, or scratching a name into a rock, humanity has exhibited the impulse to document itself, its activity, and its movement.

It’s as if these are saying:

“I exist.

Wish you were here.”

References:

- Encyclopædia britannica online, s. v. “Germany”, accessed September 10, 2013.

- Fodor, Eugene. Germany 1970. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1970.

- Hanke, Helmut. “Leisure time in the GDR: trends and prospects.” The quality of life in the German Democratic Republic. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 1989.

- “Have D-marks, won’t travel” The economist 316, no. 7667 (August 11, 1990): 52.

- Smith, Jean Edward. Germany beyond the wall. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1969.